”“Caste is anti-national because it divides the nation. We want to be national, not anti-national, for which it is important to eliminate all divisions.”

Amartya Sen

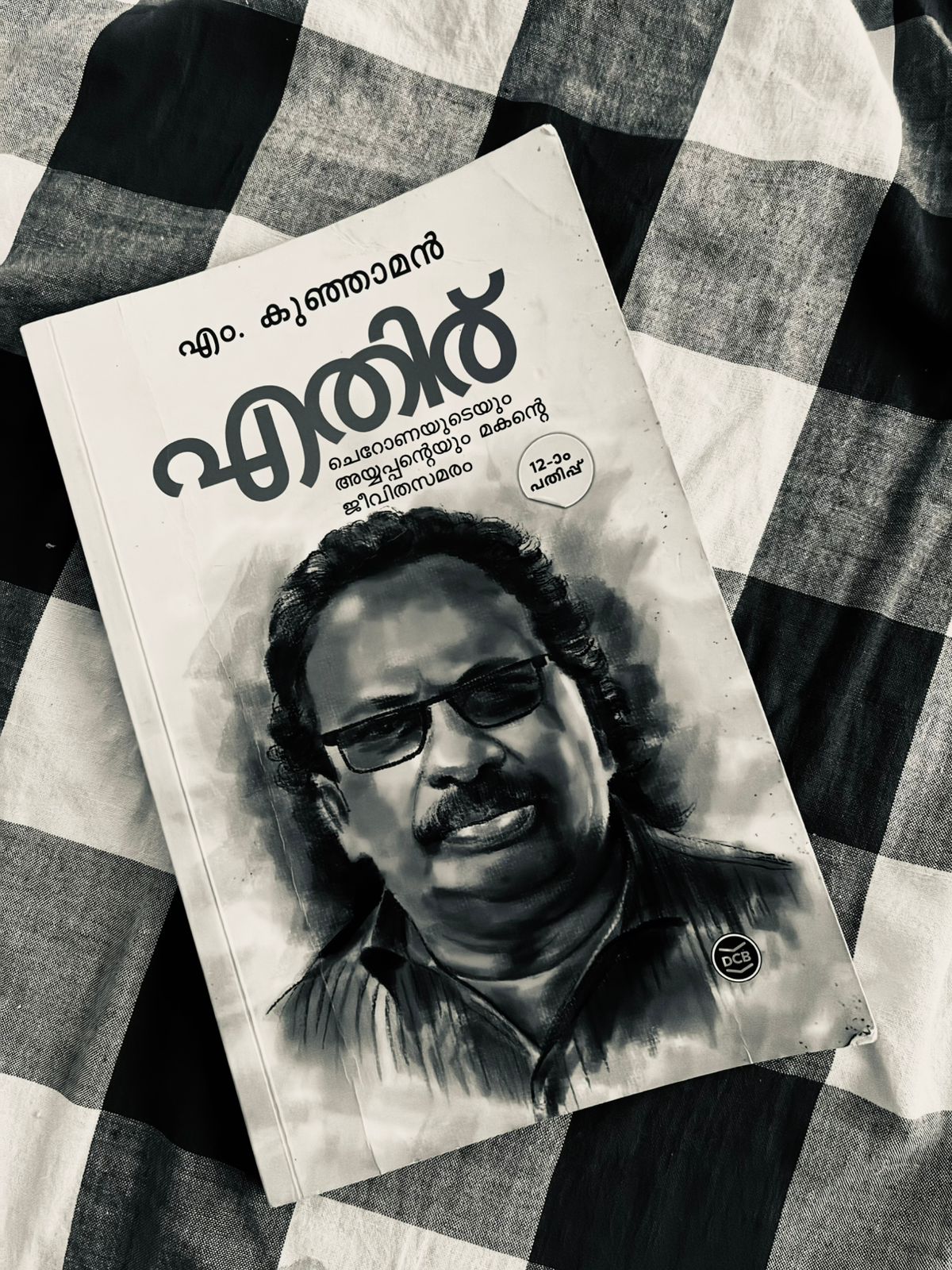

Ethiru (Opposition)—an autobiographical work by Prof. M. Kunjaman—came to my attention after his unfortunate demise last year. I was struck not only by the brilliance of the book but also by how little recognition he had received for the depth of his work and life. It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to call him the Ambedkar of Kerala. And yet, his name rarely appeared in the mainstream—perhaps a consequence of his opposition to a deeply casteist political system.

The Plot

Ethiru begins in the small village of Vadanamkurissi in Kerala’s Palakkad district, chronicling Prof. Kunjaman’s journey from rural poverty to becoming a caste economist and changemaker.

Through his story, we see the layered discrimination a Dalit faces—as a child, student, and professional. Kunjaman argues that “resourcelessness” has tethered socially vulnerable groups to the bottom of the ladder for generations. Escape, he says, takes generations to burn through.

”“resourcelessness” has tethered socially vulnerable groups to the bottom of the ladder for generations

Zero Hour

The State of Caste in India

While Marxism promises upliftment for the working class, its European origins and poor adaptation to India’s layered society have made it largely ineffective in dismantling caste structures. Land reforms, reservations, and other socialist efforts have been implemented, but their impact has often been symbolic. They pacified vote banks and gave the illusion of inclusion, while the structural dominance of upper castes remains unchanged.

Even today, the majority of influential positions—whether in governance, academia, or industry—are held by the so-called upper castes. Meanwhile, marginalised communities continue to struggle for basic living standards.

What Can Be Changed?

Capitalism—though often critiqued—offers one possibility: it values the product more than the producer. If lower castes are given access to resources and ownership of production, they may find a way out of generational stagnation. Kunjaman advocates for economic empowerment as a tool for social upliftment.

But capital alone isn’t enough. Education is crucial. Knowledge not only informs—it liberates. It reshapes identity, awareness of rights, and agency. However, Kunjaman critiques the current form of reservation, arguing that it often leaves beneficiaries feeling like subjects of charity rather than citizens claiming rightful opportunities. The psychological impact, he warns, can be lasting.

”Knowledge not only informs—it liberates. It reshapes identity, awareness of rights, and agency.

Zero Hour

I Agree to Disagree

While I resonate with Kunjaman’s economic arguments, I’m also cautious. What if the newly empowered use capital without social accountability? Will it merely replace one elite with another?

Economic empowerment must go hand in hand with social consciousness. Wealth creation for the sake of representation is not enough—there must be an ideological reshuffle of what that wealth is meant to achieve.

This brings us back to education, not just degrees, but value-driven, inclusive education that empowers historically oppressed groups to think not just upward, but outward.

A Vicious Cycle?

What comes first: capital or consciousness? It’s the classic chicken-or-egg question. We need more data to answer this with certainty. We need a new caste intelligentsia—one that is inclusive, representative, and rooted in lived realities—to guide this transition.

Ethiru opened my eyes to how dangerously limited and normalised my understanding of Indian political history was. I’ll never fully understand the lived experience of a Dalit in India, but I can—and must—learn, unlearn, and amplify.

On the other hand, even Ethiru misses perspectives—like that of women, whose struggles are often underexplored in discussions of caste. What we need is a collaborative framework of thinkers across caste, gender, and class to truly dismantle these interconnected oppressions.

Time to Act

It’s no longer enough to “hope” or “look forward.” We need to act. But action must be rooted in truth. And truth begins with unlearning the convenient lies we’ve clapped for all our lives.

There are no “them.” There’s only us. We either rise together or fall divided.